Lining up the Reasons Not to Do Something and Coming Up with Reasons to Do What Doesn't Need to Be Done

Class of 2007

In retrospect, I’ve taken a long route. I graduated from school in March 2007, and started working at Mori Building Co., Ltd. Learning at the seminar conducted by Prof. Akira Morita about Private Finance Initiative (PFI), which is a scheme where private firms are contracted to complete and manage public projects, inspired in me a desire to know more about the process of how private firms create public spaces while dealing with the government.

A seminar camp with Prof. Morita in Sawara City (now Katori City), Chiba

The 2008 global financial crisis occurred the year after I joined the company. I was quite fortunate to have been in the hands of Mori Building while all of the emerging real estate firms were going out of business (It wouldn’t have worried me if I fell back on the government job for which a lot of GraSSPers aim). Since the management seems to have liked unusual personnel, a few years later I found myself working at the management planning division where I was given an environment that enabled me to discuss multibillion-dollar investments or the future of a company. Looking back, my ego might have been sky high.

Then, the Great East Japan Earthquake happened, and it took my ego down a notch. It’s still fresh in our minds, and we had just never experienced anything like that before. My office was located in the building complex called Roppongi Hills. Fortunately, it wasn’t greatly damaged in accordance with its slogan for earthquake and disaster preparedness. In fact, there’s an enormous in-house power generator that’s not for emergencies installed in the basement of Roppongi Hills. It’s so reliable that it cannot only supply power without buying electricity from Tokyo Electric Power Co., Inc., but also sell electricity to others. That experience happened to show me what I had always wanted to know, the importance of the private sector in playing public roles. And yet at the same time, I become painfully aware of how powerless human beings were before the tsunami and nuclear accidents.

I visited Fukushima and Miyagi prefectures as a volunteer a few times after the earthquake. In the meantime, I started to realize that the front-line of town development would be evident there in those affected areas. After seeing young people sharing the spirit of “making the most interesting town in the world” at places where they’ve lost everything, I couldn’t help but jump into it. I eventually chose to make a career move to an American NPO and relocate to Ishinomaki City in Miyagi.

A project that I supported after moving to Tohoku

A lot of things happened since then. Of course, the whole experience was rewarding, and I even left a small mark there through a few building projects. But whenever I had meetings on Skype with the headquarters in San Francisco and sponsors in New York, it was quite challenging for me to argue with them in English at around four or five o’clock in the morning. The headquarters of the NPO went bankrupt shortly after I left the organization, but that’s life.

I’m actually taking the long way around in writing what I’m trying to say. Maybe it’s just my imagination.

I’m currently working as a researcher at a think tank in Osaka. The work mainly involves administrative consignment projects, where I research and support the creation of various plans prepared by local governments. As I also help with the work for the central government, I’m sort of a ghostwriter of the industry that I once, for a brief moment, thought of pursuing after graduating. The wheels of fortune keep turning.

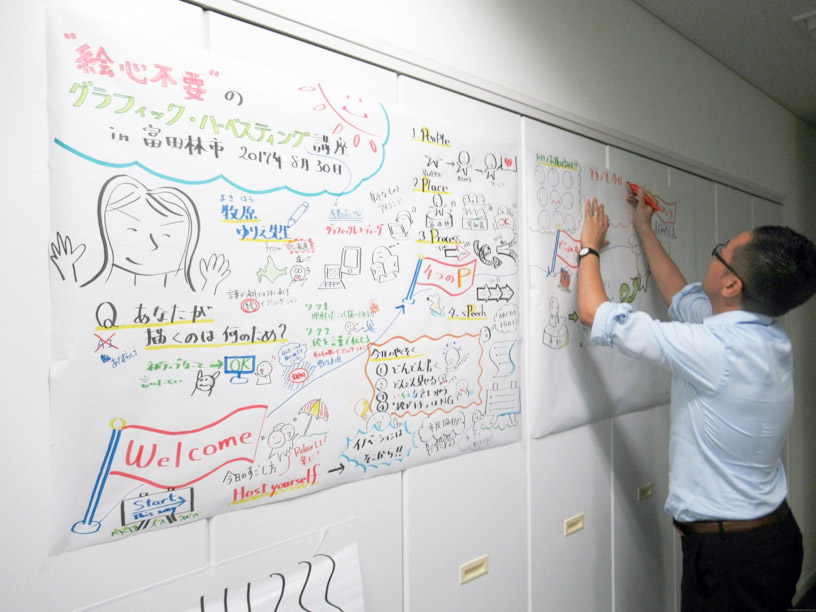

What I’ve found very interesting recently is the process of reflecting on the opinions of the locals in their policies. The technique of opening a workshop and facilitating discussions between the people there and the administration has rapidly become popular in the past ten years, and its importance is getting better understood. I personally enjoy using graphics (pictures) to organize meetings and discussions, so I often go out to various places and draw pictures.

Organizing discussions by drawing graphics (pictures)

I’m at the bottom right

Now that you’ve read this far, have you noticed that the foreshadowing in the title hasn’t quite been explained yet?

Well, let me start explaining. While supporting administrative work, I’ve found that they had two types of work. The first is to line up the reasons not to do something. Administrative resources and budget are limited. Also, their authority is determined by law. It’s natural that there are things they can and can’t do. The second thing is to come up with reasons to do things that you don’t really need to do. Their job is to put things in the rules of administrative planning and budget enforcement in order to surmise what the administrative heads come up with and then execute their plans. Just so there’s no confusion, I’m not trying to criticize the government. I think the jobs there are extremely important, and the world wouldn’t turn if there were no one to work on them. Therefore, I’m grateful for it.

However, work and career do not necessarily turn out the way you envisioned. An earthquake might come, or the company you work for might go bankrupt (even government employees have no guarantee). Nevertheless, it’s worthwhile to get the best from yourself to try to achieve your goals in the place of your own choosing. I wrote about the two types of work earlier, but of course, they aren’t everything. As for the third, I would like you to find a job that both you and people around you can enjoy, and I want to continue working like this too.