The higher temperatures brought about by UHI stem from a combination of effects, including greater absorption of heat in road and building materials, ‘canyon’ heat-trapping of tall structures, and waste heat from cars and facilities. Exacerbated by climate change, heat-related stress and mortality risk will increasingly pose a hazard for the world’s cities, which accommodate a growing majority of the population.

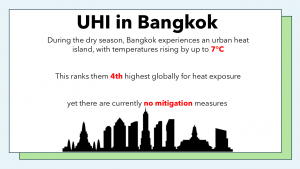

To anyone who has had the chance to visit Thailand’s modern-day metropolis, the implications of UHI might be enough to trigger more than a few tropical flashbacks. During its infamous dry season, UHI raises temperatures in Bangkok another 6–7°C, awarding it the fourth highest for heat exposure in the world. Causes for such extreme conditions include limited green space, poor urban design, extensive air conditioning and high vehicle emissions. In light of the dire predictions of climate change, what Bangkok is experiencing today potentially foreshadows a fate awaiting many other cities in the world. Hence, the Bangkok government faces an opportunity to set a precedent which other regions, particularly those in Southeast Asia recognised to be highly climate vulnerable, could follow great interest.

To anyone who has had the chance to visit Thailand’s modern-day metropolis, the implications of UHI might be enough to trigger more than a few tropical flashbacks. During its infamous dry season, UHI raises temperatures in Bangkok another 6–7°C, awarding it the fourth highest for heat exposure in the world. Causes for such extreme conditions include limited green space, poor urban design, extensive air conditioning and high vehicle emissions. In light of the dire predictions of climate change, what Bangkok is experiencing today potentially foreshadows a fate awaiting many other cities in the world. Hence, the Bangkok government faces an opportunity to set a precedent which other regions, particularly those in Southeast Asia recognised to be highly climate vulnerable, could follow great interest.

Yet, despite all the incentives to address the problem, the Thai and Bangkok administrations have shuffled their feet, stifled by weak governance, economic priorities, and bureaucratic obstacles. The challenge marked by the BangCool proposal is to find long-term solutions to the fragmentation of governance and lack of collaboration with private stakeholders, and devise a process to align the interests of each party. At the same time, it aims to promote public awareness of the critical effects of UHI, particularly in low-income communities in densely urbanised areas who are disproportionately vulnerable.

Thailand’s national policy for land use has a history which can be summarised as passive. An official was once quoted as admitting “our department focuses more on economic rather than environmental priorities”. At a local level, the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) has several divisions assigned to heat adaptation; however, collaboration is rare, and no policy directly addresses the problem of UHI. Its City Planning Department’s “comprehensive” 2013 urban land use plan notably failed to protect its remaining green space, due to a lack of cross-departmental communication and insufficient fines for breaches.

Compounding the problem is Bangkok’s private sector, which has little history of engaging with environmentally friendly building projects. Bangkok is provides a golden example of the notion “Whenever there is a chance to turn a piece of land into a commercial space, developers always build the maximum.” It is clear that more proactive leadership is needed to issue incentives to developers to drive long-term countermeasures to UHI.

The student team’s proposal details a pilot to initiate this key public-private linkage, aiming to serve as a model for natural cooperation that can propagate throughout society. In the first phase, a task force will be assigned to spread awareness of the problems of UHI and their possible solutions. As a lack of public understanding was cited as hindering progress in the past, it is important to facilitate greater local community involvement and fair oversight of the infrastructure development process. This phase will include a study between local authorities and private developers to prove the concept of this collaboration, including subsidies for measures such as painting roofs white and planting vegetation.

The outcomes will be used in the second phase to implement incentives for businesses, including a rating system for sustainable buildings and revised purchasing criteria for public procurement. Again, transparency and involvement of stakeholders from the start of discussions will be key to effective adoption. Noting other similar initiatives which have been successful in the past, the implementation strategy includes forming partnerships with local universities, NGOs and the private sector, recruiting volunteers from local colleges and communities, and involving real estate developers for innovative UHI measures.

In the pilot’s implementation, BangCool would aim to cover 3,000 residential roofs in one of Bangkok’s hotspot districts, such as Udom Suk, Khlong Toei or Huai Khwang. Monitoring and evaluation will be facilitated by installing temperature sensors and energy meters in selected homes while collecting feedback from residents. For funding, the initiative will appeal to local government, the private sector and international bodies which have previously backed UHI initiatives.

In the pilot’s implementation, BangCool would aim to cover 3,000 residential roofs in one of Bangkok’s hotspot districts, such as Udom Suk, Khlong Toei or Huai Khwang. Monitoring and evaluation will be facilitated by installing temperature sensors and energy meters in selected homes while collecting feedback from residents. For funding, the initiative will appeal to local government, the private sector and international bodies which have previously backed UHI initiatives.

Regarding the crucial issue of division of responsibility, clear lines between national government ministries and the BMA will be drawn, discouraging developers from circumventing land use planning regulations. Furthermore, centralizing information on land use and infrastructure projects in the city offers considerable value to the BMA. Integrating this data with advanced technologies such as remote sensing and satellite imagery will enable local authorities to pinpoint areas of Bangkok’s highest at risk from UHI, facilitating targeted intervention strategies.

Indicators to evaluate the proposal’s outcomes can be regularly monitored along the results chain, spanning from green rating building awards and reduced heat-related hospitalisations and deaths in the short-term, to improved health metrics and increased private sector investment in the long-term.

While the team has tailored the aims of BangCool to address specific needs of the local community, the project’s inclusive collaborative infrastructure can scale to Bangkok’s 50 districts and other cities internationally. Similarities in geography, demographics and socio-economics in South and Southeast Asian regions mean that Bangkok could set a standard in UHI mitigation, as well as provide an iterative model to deal with a range of pubic-private policy problems.

As proven by its chequered history, effective management of Bangkok’s UHI problem is not a simple matter of funding urban infrastructure projects. A sustainable, long-term solution requires a process that ensures buy-in from the government, developers and local communities while reducing misalignment between stakeholders. The team’s solution in the Bangkok Cooling Initiative would positively influence the design of infrastructure through data-driven and locally-led prioritisation. The fruits of such cooperation would not only herald a new era in green development, but allow in the air for much-needed community perspectives on living together with businesses, governments, and a global future.

(Edited by Clement Ng)

This blog post was originally written as a proposal to the 2024 Global Public Policy Network Conference by a student team at GraSPP (Junya Eriguchi, Emily Murnane, Bradley Murray, and Taishin Noble) in December 2023.

The full version is available from the link below.