To reach Thailand’s goal of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2065 (Global Climate Promise, 2022), transportation is a key sector for policy renewal. On top of its aims to introduce 1.2 million electrical vehicles (EVs) by 2030, the government faces many challenges including creating EV infrastructure, promoting sustainable fuel blends among consumers and dealing with the millions of energy inefficient end-of-life vehicles in circulation.

As the world’s fifth largest producer of motorcycles, decades of protectionist policies since the 1960s have allowed Thailand to expand its production capacity to 3.66 million per year. A ubiquitous sight and sound across the country, motorcycles have been widely favoured for their convenience, ease of use and affordability. Data from the Department of Land Transport (DLT) revealed that from 2010 to 2019 nearly 2 million new motorcycles were registered per year, with the current total at over 21 million. While 84% of operating motorcycles are compatible with 20% ethanol blended fuel (E20), the remaining 3.1 million can only run on 10% ethanol blended fuel (E10) and unleaded gasoline, the worst offending fuels in terms of carbon dioxide emissions.

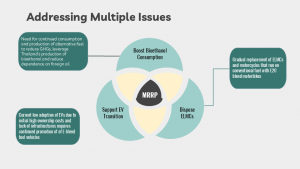

Considering this, the GraSPP team tailored their proposal to address two major environmental concerns in Thailand’s transportation outlook. Named the Motorcycle Renewal and Recycling Program (MRRP), it provides an easy-to-integrate framework for recycling end-of-life motorcycles and promoting bioethanol consumption, using a small-scale pilot project implemented in the region of Ayutthaya, north of Bangkok. Their strategy presents an inclusive scheme that engages with all stakeholders, from government departments to oil and gas production companies and motorcycle recycling and secondhand shops.

Considering this, the GraSPP team tailored their proposal to address two major environmental concerns in Thailand’s transportation outlook. Named the Motorcycle Renewal and Recycling Program (MRRP), it provides an easy-to-integrate framework for recycling end-of-life motorcycles and promoting bioethanol consumption, using a small-scale pilot project implemented in the region of Ayutthaya, north of Bangkok. Their strategy presents an inclusive scheme that engages with all stakeholders, from government departments to oil and gas production companies and motorcycle recycling and secondhand shops.

Although the data on current methods of motorcycle disposal in Thailand is limited, the team was able to identify risks to the environment posed by existing local practices. Second-hand vehicles are very popular in Thailand, with approximately 2 million registration changes per year. Giving rise to a used parts market of approximately 30,000 stores, under current practices the disposal of unusable parts presents issues such as the emission of used oil/liquids from the dismantling process and CFC into the atmosphere.

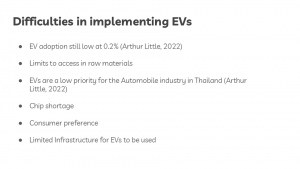

Meanwhile, Thailand’s energy and trading landscape also shapes the path to sustainability. Despite tax incentives for EV component procurement introduced by the government, current EV adoption rates are still at a low 0.2%. From a production perspective, limits to access to raw material affects the EV supply chain. Thailand’s competitive advantage as the automotive hub of Asia may be lost as it becomes an assembly engine forced to use lithium cells imported from overseas. The industry is also greatly beholden to the policies of the Japanese original equipment manufacturers accounting for 80–90% of automotive production, who consider the EV as a low priority due to their belief in a more gradual transition from the gasoline powertrain. From a consumer perspective, there is currently a greater preference for non-EVs due to the initial cost, excerbated by rising battery costs and semiconductor chip shortages. The minimal gap in price for electricity versus fuel in Thailand also contributes to slower than global EV adoption, which itself is expected to only account for 50% of total vehicles by 2050.

Meanwhile, Thailand’s energy and trading landscape also shapes the path to sustainability. Despite tax incentives for EV component procurement introduced by the government, current EV adoption rates are still at a low 0.2%. From a production perspective, limits to access to raw material affects the EV supply chain. Thailand’s competitive advantage as the automotive hub of Asia may be lost as it becomes an assembly engine forced to use lithium cells imported from overseas. The industry is also greatly beholden to the policies of the Japanese original equipment manufacturers accounting for 80–90% of automotive production, who consider the EV as a low priority due to their belief in a more gradual transition from the gasoline powertrain. From a consumer perspective, there is currently a greater preference for non-EVs due to the initial cost, excerbated by rising battery costs and semiconductor chip shortages. The minimal gap in price for electricity versus fuel in Thailand also contributes to slower than global EV adoption, which itself is expected to only account for 50% of total vehicles by 2050.

On the other hand, since the identification of reliance on foreign oil as a major concern, Thailand’s domestic bioethanol production has grown as a sustainable solution to energy security. The country is the largest sugarcane producer in Southeast Asia and fourth in the world, and well positioned to commercialize ethanol as a biofuel for the transportation sector. E20 fuel, with its 20% mix of ethanol, produces less carbon dioxide upon combustion. Thailand energy authorities signaled the adoption of gasohol E20 as the primary oil fuel at petrol stations instead of E10, setting subsidies and levies to encourage domestic transition. However, a widespread conception among the public that a higher ratio of ethanol may degrade vehicle engines must also be addressed for this to occur.

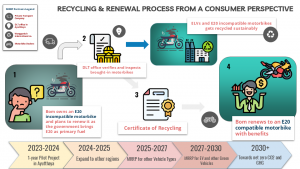

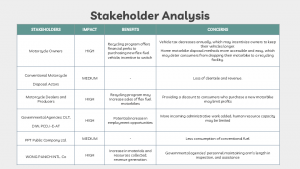

The key strategy behind MRRP is to incentivize consumers to dispose of their E10 and unleaded gasoline end-of-life motorcycles while utilising an existing network of facilities and actors. Ayutthaya was chosen for the pilot project for its high concentration of various important vehicle recycling stakeholders, who assembled around its large second-hand vehicle parts market comprising approximately 200 shops. This includes Wong Panich, one of the country’s major vehicle disposal facilities.

In the implementation, owners who are notified by the DLT that their motorcycles have entered end-of-life can voluntarily attend an inspection by certified technicians for carbon emissions and recycling or scrapping suitability. Once program eligibility is confirmed, the DLT will issue a subsidy certificate for the purchase of an E20/E85 compatible motorcycle in the country. In addition, an extended warranty would be granted alongside this subsidy to allay fears of ethanol corrosion to the vehicle.

In the implementation, owners who are notified by the DLT that their motorcycles have entered end-of-life can voluntarily attend an inspection by certified technicians for carbon emissions and recycling or scrapping suitability. Once program eligibility is confirmed, the DLT will issue a subsidy certificate for the purchase of an E20/E85 compatible motorcycle in the country. In addition, an extended warranty would be granted alongside this subsidy to allay fears of ethanol corrosion to the vehicle.

End-of-life motorcycles are then collected by private recycling/scrappage companies for processing by the pilot project partner, Wong Panich. To ensure that the motorcycle is disposed of in an environmentally friendly manner, technical advice will be provided with regular inspections during the pilot project life by the Pollution Control Department, Department of Industrial Works and external consultants.

In addition to the above stakeholders, the state-owned development company PPT Public Company will be drawn on for their expertise in the oil and energy sector. The project impacts both the company’s existing gasoline production business and stake in the developing biofuel industry, and as such PPT can play a key role in monitoring the pilot outcomes.

Notably, MRRP’s approach has been designed to be compatible with Thailand’s existing governance structure and stakeholders. The fact that the Thai government already maintains a similar approach to regular garbage recycling and disposal (through public-private partnerships) ensures the project will find a comfortable home.

The expected outcomes of the project will provide valuable feedback to all concerned stakeholders for the government’s upcoming regulatory framework for end-of-life vehicles, which will require enforcement of inspection rules, restructure of vehicle taxation, private-public partnerships with scraping facilities, creation of specific standards and implementation of financial incentives. Finally, contributions to carbon reduction and financial successes from the project will propel the waste management industry into the limelight, inciting entrepreneurs to invest and venture into this increasingly important domain.

The MRRP project is an example of how the local operations of multiple stakeholders can be connected in a movement to address a global dilemma, from agriculture and manufacturing to transportation, trade and finance. Having witnessed years of ASEAN development, the time could be right to spotlight Thailand’s flying geese bioethanol movement, sparking discussion in academic and trade-related spheres as more nations seek to replicate Thailand’s success.

(Edited by Clement Ng)

This blog post was originally written as a proposal to the 2023 Global Public Policy Network Conference by a student team at GraSPP (Moe Furukado, Hiroki Ito, Emily Zhu and Kavin Pillai) in December 2022.

The full version is available from the link below.