“I still extract the underground water although the colour is yellow… After using a filter, it looks better, but it is still not drinkable. However, I do not have any choice but [to] use it for brushing my teeth and taking a bath every day.”

— Shanti Wira, Jakarta Citizen

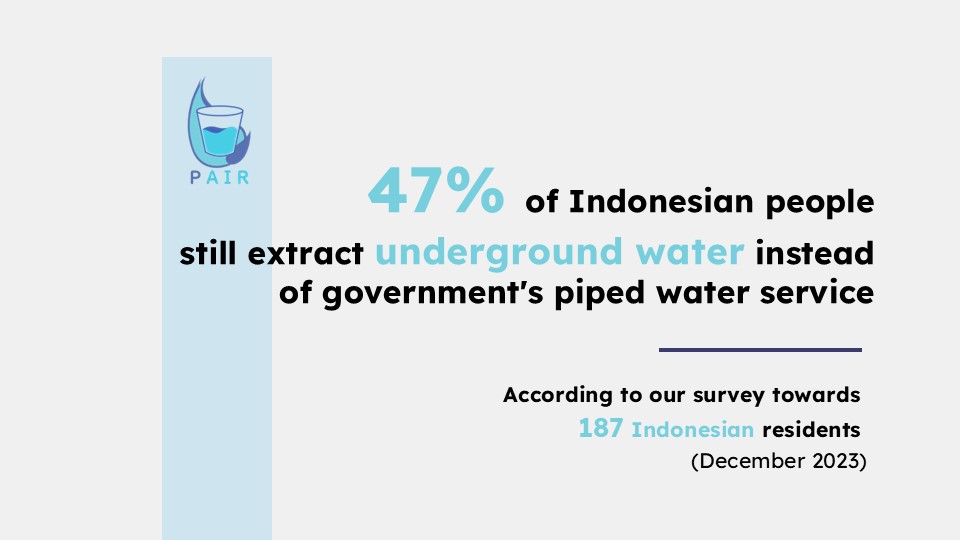

Jakarta, the capital region of Indonesia, is an area subject to extreme rainfall and flooding. Today, it experiences significant land subsidence due to several unchecked human factors and climate change, among which is widespread unregulated groundwater use. Despite being exacerbated by modern day issues, the government still only provides enough piped water to supply 65% of the Jakarta populace. In its public opinion surveys obtaining responses from 187 Indonesians, the GraSPP team found that about 47% currently still relied on groundwater to survive.

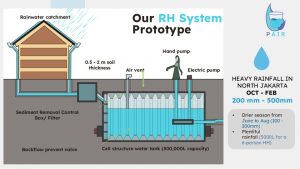

To address this pressing issue, the team has proposed the installation of an underground rainwater harvesting (RH) system in Kampung Luar Batang, North Jakarta—a village that is currently 60–100 cm below sea level. Their pilot project “Program Air Bersih Rainwater Filter” (“bersih” means “clean”) or PAIR includes a partnership with a manufacturer of RH technology, as well as a Government Taskforce to implement and monitor the project in accordance with community feedback. They believe these will be the necessary ingredients to spread similar initiatives across North Jakarta to help protect vulnerable communities from worsening climate conditions.

In preparing their proposal, the team reviewed the main RH policies and projects in Indonesia to identify key issues to the problem. The history of RH trials conducted by the North Jakarta government is an obscure one, with current projects limited to temporary programs administered by academia. As such, no enforced national standardisation currently exists, despite building safety issues and risk of contamination from reservoirs in above-ground tanks.

To refine their policy, the team used three types of data collection techniques directly involving residents in Indonesia: (1) public opinion surveys, (2) ethnographic interviews and (3) discourse analysis. The result of the surveys conducted via social media (1), mentioned above, affirmed the extant of underground water extraction by the populace. The social media account used has 30,000 followers, this number will be referred as the population (N) of the team’s 187 respondents—sample (s). For a more detailed insight, interviews (2) were conducted with local stakeholders such as academia, NGOs, and Indonesian residents, which highlighted reasons for ongoing underground water use such as its low-cost of extraction. Finally, they analysed academic journals, papers, and news articles on rainwater harvesting policies to better understand the impact of potential solutions.

Their proposal of an underground RH system in a government-owned elementary school facilitates is aimed to smooth administrative application and increase community participation in the project. Totetsu, a provider of United Nations Industrial Development Organization-backed RH technology, was chosen as a manufacturing partner. The company’s experience will help ensure durability of the facility, accessible maintenance and high standard of filtration. Advantages to the proposed system include reduced contaminants compared to above-ground tanks and near zero operational cost compared to sea and wastewater purification processes. At the same time, RH reduces the impact of heavy rainfall by capturing surface runoffs.

The proposed Government Taskforce will conduct monthly check-ins with the community and project site, as well as promote maintenance awareness through training courses. A renumeration scheme could also be used, incentivising households through payments of $0.4 for every 1000 litres harvested. Community needs can be assessed through interviews, surveys, and arranged public forums, supported by the NGO People’s Coalition for the Right of Water (KRuHA). This bottom-up approach is crucial to understand the gaps in water access, informal water trade, and average water consumption per household from a local perspective. Grass roots representation will be ensured by engaging with locality chiefs as well as other local organisations (CBOs).

For monitoring, key performance indicators (KPIs) will be utilised to evaluate RH system operation, service quality, and calculation of water costs saved. In the past, lack of coordination and use incentives has resulted in community mistrust of rainwater quality and hygiene standards, leading RH systems to fall into disuse. In the PAIR proposal, the community will be involved in activities from data collection to reporting water bills, quality and reliance, impact on surface runoff, and future KPIs. Furthermore, to facilitate quality and safety measures of future RH systems in Indonesia, a standardised RH permit will be established, which could prove useful for other regions with similar climate conditions around the world.

Where projects in the past have faltered through low-budget and low-resource models, the PAIR team is confident that its proposal’s emphasis on long-term, comprehensive investment will answer the urgent call for a practical water accessibility solution in North Jakarta, Indonesia. The project aims to improve awareness and maintenance knowledge of rainwater harvesting in the community through community-based participation; thereby, it will improve uptake and viability. Through a smart coordination of existing local stakeholders, PAIR’s vision of using rainwater has the potential to benefit climate adaptation—rather than exacerbate it—and could herald the new beginnings of clean water availability in similarly affected regions around the world.

(Edited by Clement Ng)

This blog post was originally written as a proposal to the 2024 Global Public Policy Network Conference by a student team at GraSPP (Emily Fursa, Mei Mitsui, Vania Putri Andriani, Yuta Sato) in January 2024.

The full version is available from the link below.